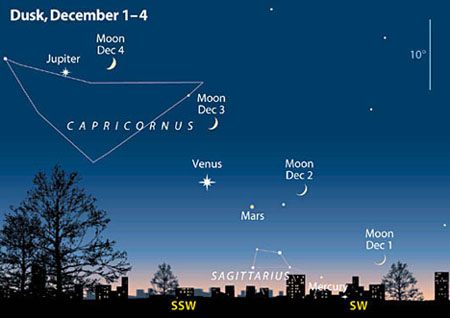

FRESNO - As twilight falls each evening in the Westerly sky above the City this week, look south for the Moon. From the 1st through the 8th it makes its way past a long diagonal line of planets.

On the 1st the thin waxing crescent stood above and to the right of Mercury, which was almost down on the horizon (try binoculars). On the 2nd and 3rd the Moon passed faint Mars and brilliant Venus. By the 4th the Moon, was a thick crescent, is off to the right of bright Jupiter. Four nights later, by the 8th, the now-gibbous Moon will be very near Saturn. Also in the line, but too faint to see without binoculars or a telescope, are Uranus and Neptune

This month, all nine planets cluster together in one small swath of

the sky. My new friend's neighbor has a cat with the same name as mine.

My stepdaughter in New Jersey and a psychologist friend in L.A. are

expecting a baby on the same day.

Are these portentous cosmic occurrences? Or merely curious

coincidences?

It's not an idle question. Much of science involves trying to

determine which events are connected by common causes, and which are

linked only by the luck of the draw.

'In mathematics, in science, and in life, we constantly face the

delicate, tricky task of separating design from happenstance,' writes

Ivars Peterson in his latest book, 'The Jungles of Randomness: A

Mathematical Safari.'

Is a cluster of cancer cases in McFarland, CA the result of toxic

residues, or a normal blip in the distribution of disease? Are those

black spots in the photograph evidence that house-sized snowballs are

raining on Earth, or random noise in the detector?

Mathematics can help sort out these scenarios. Indeed, a little

mathematical know-how may be the only known antidote to a pervasive

frailty of the human mind: the perception of causes and connections

behind purely chance events.

As Peterson, the mathematics and physics editor for Science News,

points out, human beings are programmed to perceive patterns in chaotic

events - the better to make sense of an often confusing visual world. They

see forms in cracks on the ceiling, faces on the moon, woolly sheep in

clouds. They group clusters of adjacent stars into images of warriors and

serpents and dippers in the sky.

'Humans are predisposed to seeing order and meaning in a world that

too often presents random choices and chaotic evidence' he writes.

Indeed, most amazing coincidences are created in the mind - like the constellations in the sky - from the human tendency to find plausible

links between objects and events.

Consider two strangers sitting in adjoining seats on airplane. What

are the chances that they will have something in common?

Given the vast number of possibilities - from shared favorite authors

to hometowns, past lovers and current jobs, schools and acquaintances - it

can be shown that in 99 times out of 100 the two passengers will be

linked in some way by less than two intermediaries, according to

mathematician John Allen Paulos.

The number of things the two people don't share will vastly outweigh

the number of things they do. But only the shared links will be

remembered as amazing coincidences.

The same is true, Paulos says, of prophetic dreams. Often, people will

dream about, say, an earthquake or a plane crash, only to read in the

paper the next day that it actually happened. But given the fact that

roughly 250 million people in the U.S. spend several hours in dreamland

each night, 'we should expect as much. In reality, the most

astonishingly incredible coincidence imaginable would be the complete

absence of coincidence' he said.

Sometimes, coincidences do point to deep truths. Einstein, for

example, was bothered by the well-known fact that gravity and inertia

balance out exactly in our universe. That is why a bowling ball and a

golf ball dropped from a high shelf hit the ground at the same

time--because while gravity pulls harder on the bowling ball, inertia

endows the bowling ball with a greater resistance to being pulled.

Einstein thought this uncanny equivalence had to be more than a funny

coincidence - and came up with the idea that both gravity and inertia are

aspects of a bigger picture - the curvature of space-time.

In the same way, there is a lot more than coincidence behind the fact

that more smokers than nonsmokers get lung cancer. Sometimes coincidence

does point to a cause.

How can one tell the difference between coincidences based on cause

and those based on chance? Statisticians use all kinds of filters to

determine which is which, but even the mathematically immune can use some

easy tricks to keep from getting fooled.

For example, they can remember that large numbers of anything are

bound to create coincidences. For example, it is certain that at least

250 of the 250 million people living in the United States will experience

a one-in-a-million coincidence every day - purely by chance.

And while the odds that any one person will win the lottery twice in

the same year is astronomical, the percentage that any of the millions of

previous lottery winners will win another lottery in their lifetime is

pretty good.

The fact is, events that people normally think of as highly unlikely

are often very likely. If someone flips a coin a hundred times, the

chances of coming up with a long string of heads or tails are more likely

than not. It's not an amazing coincidence. It's the natural order of the universe.

Comment